Edward Copeland: The Year of Robert Altman

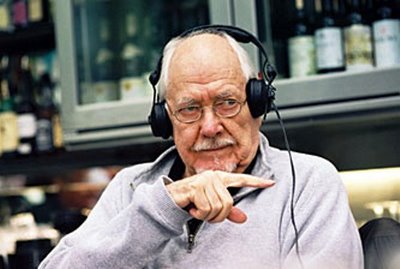

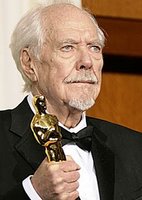

When Time Magazine, in what essentially amounted to declaring its official demise as a serious publication, named "You" (yes -- you ... and me and everyone else in the world. Can I put that on a resume?) as Person of the Year, I -- and just about everyone who doesn't work at the magazine (and probably many who do) laughed. Sure, they could have picked people who really affected the year like Moqtada al-Sadr or the batshit crazy president of Iran, but for me, there only was one choice: Robert Altman, who (on a nonpersonal level at least) hovered over my entire year as no other. It began early, on Jan. 11, with the announcement that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences finally would bestow upon the great director an honorary Oscar after missing the chance on five occasions (for MASH, Nashville, The Player, Short Cuts and Gosford Park) to give him the directing Oscar he so richly deserved. The movie buff-ridden blogosphere exploded with joy, with more than a few echoing my sentiment of "About damn time!" On Feb. 21, the proprietor of this blog declared a blog-a-thon in Altman's honor to be held the weekend of the Oscars.

Many couldn't wait that long and, in the lead-up to Altman's honor, premature tributes appeared all over the Internet. Among them: Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule's proprietor Dennis Cozzalio, who offered an exhaustive and personal two-part look at his career in honor of Altman's 81st birthday. "I was first exposed to the work of Robert Altman, whose 81st birthday it is today, at around age four or five, and I, of course, had no idea I had been exposed at all," Dennis wrote, later noting that his inability to see the movie version of MASH led to one of his first "movie crushes" as well as to his discovering Pauline Kael's film criticism. I, too, plead guilty to jumping the blog-a-thon gun, but as That Little Round-Headed Boy wrote, "...how can an Altman fan quibble about paying no attention to the rules?"

Many couldn't wait that long and, in the lead-up to Altman's honor, premature tributes appeared all over the Internet. Among them: Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule's proprietor Dennis Cozzalio, who offered an exhaustive and personal two-part look at his career in honor of Altman's 81st birthday. "I was first exposed to the work of Robert Altman, whose 81st birthday it is today, at around age four or five, and I, of course, had no idea I had been exposed at all," Dennis wrote, later noting that his inability to see the movie version of MASH led to one of his first "movie crushes" as well as to his discovering Pauline Kael's film criticism. I, too, plead guilty to jumping the blog-a-thon gun, but as That Little Round-Headed Boy wrote, "...how can an Altman fan quibble about paying no attention to the rules?" Then, when the actual Oscar weekend arrived, the real blog-a-thon hit like a hurricane with insightful, personal and probing posts appearing across the World Wide Web. Brian Darr at Cinemarati offered his own Altman Oscars. Wagstaff at Liverputty (and a frequent contributor here and at my site as well) looked closer at Altman's use of nudity. At The House, Matt Zoller Seitz interviewed Deadwood creator David Milch and spotted what should have been obvious to many of us -- the influence of McCabe & Mrs. Miller on Milch's great, now lamented HBO Western. When Oscar night came, Altman's gracious speech was without a doubt the highlight. He revealed what few people knew -- that he'd been the recipient of a heart transplant 10 years before from a young woman, and offered a prediction that sadly proved inaccurate: that he had many more years of filmmaking to come. As a final touch to infuriate Crash haters everywhere, Paul Haggis' obviously Altman-influenced film won Best Picture that night, something Haggis wrote specifically about in a year-end eulogy in Entertainment Weekly.

Then, when the actual Oscar weekend arrived, the real blog-a-thon hit like a hurricane with insightful, personal and probing posts appearing across the World Wide Web. Brian Darr at Cinemarati offered his own Altman Oscars. Wagstaff at Liverputty (and a frequent contributor here and at my site as well) looked closer at Altman's use of nudity. At The House, Matt Zoller Seitz interviewed Deadwood creator David Milch and spotted what should have been obvious to many of us -- the influence of McCabe & Mrs. Miller on Milch's great, now lamented HBO Western. When Oscar night came, Altman's gracious speech was without a doubt the highlight. He revealed what few people knew -- that he'd been the recipient of a heart transplant 10 years before from a young woman, and offered a prediction that sadly proved inaccurate: that he had many more years of filmmaking to come. As a final touch to infuriate Crash haters everywhere, Paul Haggis' obviously Altman-influenced film won Best Picture that night, something Haggis wrote specifically about in a year-end eulogy in Entertainment Weekly. The Altman honor prompted me to try to catch up with many of his films on DVD, some of which I hadn't seen, others that I had, though usually not in the proper aspect ratio the way God intended. It was a journey that took me back to A Wedding and ended last week with O.C. and Stiggs. Some holes still remain in my Altman film knowledge -- I still haven't seen Brewster McCloud or Popeye, among others. June brought the wide release of A Prairie Home Companion, a film on which Altman's health was so frail that insurers insisted Paul Thomas Anderson be on hand as a backup director should anything happen. When I saw the movie, it seemed to me to be a light-hearted example of Altman directing his own eulogy and summarizing his career. I didn't know that he had told The Associated Press at its premiere that "this film is about death," much less how accurate my description would prove to be.

The Altman honor prompted me to try to catch up with many of his films on DVD, some of which I hadn't seen, others that I had, though usually not in the proper aspect ratio the way God intended. It was a journey that took me back to A Wedding and ended last week with O.C. and Stiggs. Some holes still remain in my Altman film knowledge -- I still haven't seen Brewster McCloud or Popeye, among others. June brought the wide release of A Prairie Home Companion, a film on which Altman's health was so frail that insurers insisted Paul Thomas Anderson be on hand as a backup director should anything happen. When I saw the movie, it seemed to me to be a light-hearted example of Altman directing his own eulogy and summarizing his career. I didn't know that he had told The Associated Press at its premiere that "this film is about death," much less how accurate my description would prove to be.

The day we all knew was inevitable came on Nov. 21, as Altman shuffled off this mortal coil. What a few months earlier had been celebration across the Net turned into impromptu communal mourning. Ross Ruediger at The Rued Morgue who had, just a month or so earlier, expressed such excitement at the news that Altman's next project would be a fictional adaptation of the documentary Hands on a Hard Body, mourned the loss not only of the filmmaker but of the film he wouldn't get to make -- a film that was, of course, but one item on a long list of projects that never came to fruition. I still long to have seen what Altman's Angels in America would have looked like, or to have had access to the long-fabled nine-hour cut of Nashville, or to have learned his ideas for a sequel to what I consider his greatest film. When I had the chance to interview Altman in connection with the release of Ready to Wear (or Prêt-à-Porter for sticklers), of the many things he said, one stood out for me at the time of his death.

"I find that all of these films are like your children and you tend to love your least successful children the most, but they're finished and the cord's cut and it's out there and it ... doesn't belong to me anymore."Altman and his films always will belong to us, even if the great man himself isn't here anymore to provide new ones, and nitwits such as Emilio Estevez make lame-assed attempts to imitate him in dumb movies like Bobby. Matt titled his blog-a-thon post "Altman -- now more than ever," a takeoff on the movie studio's slogan in The Player. We do need Altman now more than ever, but we'll have to soldier on and make do. He was one of a kind.

______________________________________________________

Edward Copeland is a contributor to The House Next Door and the publisher of Edward Copeland on Film and the political blog Copeland Institute for Lower Learning.

2 Comments:

Thank you, Edward - a fine piece. That quote really is something special. It's something a lot of other filmmakers could take note of, because it's indicative of Altman's humility and respect for the audience. Many of the more popular film artists today are making films for themselves more than anyone else; this self-indulgence will eventually destroy them, and its near total absence in Altman's career is why he has remained relevant and revered through decades (despite the flops, failures and misunderstoods).

Very nice overview, Edward. We should also remember (because Altman wanted us to, and also in honor of the late Gerald Ford) that "NIXON: Now, more than ever" was Richard Milhaus's 1972 campaign slogan, and Altman's early masterpieces ("M*A*S*H" through "Nashville") were very much steeped in the cynicism and disillusionment of the Nixon era. ("Nashville" began as a direct response to the CREEP's re-election -- look for that mocking poster on the wall of Lady Pearl's Old Time Pickin' Parlor!) And, of course, much later came "Secret Honor" as well as "The Player"...

<< Home